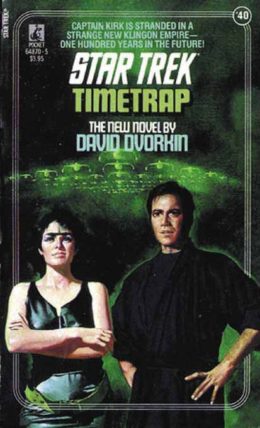

I found David Dvorkin’s Timetrap, first published in 1988, in the bottom of a moving box last week. Its cover features a particularly young and dewy-looking Kirk standing next to a woman with an incredibly impressive eyebrow in front of a fleet of Klingon Birds of Prey. The story is a subtle blend of problems: it deals with what is true and what seems to be true, with how we see the dangers around us, with the relationship between the Klingons and the Federation, and with the way the world changes over time. And my sister describes the plot as “completely bananapants.”

The basic premise of Timetrap is that Kirk is kidnapped by Klingons who try to convince him that he has travelled in time to 100 years in the future, and must return to his present with them to play a crucial role in brokering the Great Peace which will bring the Klingons and the Federation together. This, they helpfully remind him, will be the beginning of the alliance the Organians predicted back in “Errand of Mercy.” Kirk and Kor were both skeptical about it then, because they hated each other’s guts and were dedicated to depriving each other of control of Organia. As that episode reminds us, things are not always as they seem. The Klingons would like to remind Kirk of this, because their master plan—which is world-spanningly epic—is contingent upon things seeming to be other than they are. The Empire has invested a great deal of time in cultivating illusions—for example, the illusion of time travel. They didn’t go anywhen. How did they convince Kirk they did? Drugs. Lots and lots of drugs.

Kirk got himself kidnapped in the middle of an attempt to rescue the crew of a Klingon ship that was caught in some kind of space storm thing near Tholian Space. He and a security team beamed aboard the Klingon vessel, the Mauler, to attempt to rescue the crew because they believed the ship was breaking up. Instead, it completely disappeared. And then Kirk woke up on a Klingon base, where Klingon commander Morith explained “what had happened.” Kirk feels surprisingly well for a man who’s been through a shaky extraction from a damaged ship in Tholian space. His apparent health seems like it could be evidence of Klingon claims to possess advanced medical technology, or alternately, like some fairly intense painkillers. Kirk believes in option one, partly because a lot of things make sense when you’re on fairly intense painkillers. For those gaps the drugs can’t fill, Morith introduces Kirk to Kalrind, the woman who will be his new Klingon girlfriend.

Morith and Kalrind claim to be New Klingons, a group that has worked to achieve peace and suppress the aggressive nationalist impulses of the Old Klingons in favor of their enlightened acceptance of space internationalism. They claim to have been in power in the Klingon Empire for most of the century since Kirk hopped forward to their time. They’re still Klingons—they assert that a segment of the population still has warlike impulses—they still play klin zha—but they’re ashamed of the aggression that characterized Klingon culture of centuries past, and they’re past that now! They’ve got Ayleborne the Organian along for the ride to show that their intentions are truly sincere. Ayleborne may be the only character involved in this plot who isn’t drugged, because he’s also not there. Pro tip: If your super-advanced species looks like a cheap special effect, it is tragically easy to impersonate using cheap special effects.

In fact, the Klingons don’t have any special medical technology. They haven’t even patched Kirk back together very well. We will later discover that he’s roaming around—punching Klingons, taking walks, having sex—with massive internal injuries, but too high on painkillers to notice. He experiences periods of energy and euphoria followed by periods of inexplicable fatigue. He does not report any symptoms of physical trauma, including obvious contusions, abrasions, fractures, lacerations, or pain. Given McCoy’s later report on the extent of his injuries, I have to think he’s just failing to notice—our boy Jimmy is easily distracted by the ladies.

Kirk falls for Kalrind pretty hard, and finds himself surprised by “the strength and depth of his feelings for her.” Which is what they call it in the 24th century, I guess. Kalrind alleges that she is a Klingon historian. She has many, many questions for Kirk, because she’s so intensely curious about the past. Like historians are. The documents available in the Klingon archives are tragically incomplete, even after a century of sharing information with the Federation. She has a lot of gaps to fill.

If there is one thing I resent about the historians of the future proposed by the Star Trek universe, it is their failure to pursue any kind of coherent analytical perspective. They are obsessed with efforts to clarify the details of the historical narrative, which is not a horrible or worthless project, it’s just also not the sole purpose of the field—it’s overly simplistic. If you’re ever trying to figure out if someone who claims to be a historian from the future is telling the truth, all you really need to do is ask her about her dissertation. If the answer sounds like “I explained some stuff that happened” you are not talking to an actual historian (or at least, not talking to an actual historian who has any interest in having a conversation with you). We’ve already established why Kirk isn’t doing this—my best guess is that the Klingons have discovered heroin. Why is Kalrind doing this? Again, drugs.

To make a Klingon woman fall in love with, and appear lovable to, Captain James T. Kirk, you need a lot of drugs. Kalrind, we will ultimately discover, is up to her amazing unibrow in something mood-altering. This mysterious substance is also responsible for implanting her memories and personality, so I can’t compare it to a 21st century Terran product.

Although the strategies involved are limited, the scope of the Klingons’ plan is vast. Not only do they have a ship full of Klingons who have been drugged so that normal Klingons social interactions don’t alarm Kirk, they have Klingon agents spread throughout the Federation. These agents were smuggled into place and given identification papers hailing from the locations of conflicts and natural disasters that destroyed local records, rendering their identifications difficult to verify (If this seems like a twisted future argument for “extreme vetting,” please be assured that they all posed as citizens of the Federation). Like Kalrind, the Klingon agents in the Federation are using mood-controlling drugs, this time to help them pass as human. This led me to assume that everyone Dvorkin described as short-tempered was a secret Klingon—an assumption which, alas, was not borne out within the pages of the novel. I’m still convinced it’s true though. The Federation has been pretty thoroughly infiltrated, up to the highest levels. I’m not real clear on where those Klingon agents are getting their drugs. I infer that the Klingons are also into trafficking.

Like all good science fiction, Timetrap deals with the historical context of its creation just as much as the imagined future of its setting. The combination of the cultural masochism with a plot clearly intended to show young fans how drugs will make them sell out to the Klingons resonates with the era of “Just Say No!” and concerns about the future health of the East German women’s swim team (and to be fair, my memory of those concerns comes entirely from the 1994 movie, Junior). It also opens up a series of fascinating questions for readers now. Questions like “How does one carry out covert surgical repairs on a patient with internal abdominal injuries?” I thought the attending physician’s explanation for anesthesia was weak, but the lethargy caused by the patient’s internal bleeding limited the need for pre-operative counterintelligence measures. For obvious reasons, surgery itself was not described in the patient’s report, but the surgeon probably used a laparoscopic approach to minimize scarring at the incision site. The patient was permitted to over-exert himself during post-operative recovery, leading to re-injury; This, in combination with serious ethical concerns, suggests that covert approaches to trauma surgery should be used only when all other non-fatal options have been exhausted and consent can be obtained from a third party who takes responsibility for the patient’s post-operative care.

I am pleased to report that my children found my dinner table conversation about this book very enlightening, and now we all know where our spleens are—the most fun we have had with a Star Trek novel since I bribed them to eat pizza crust-first as part of the research for my review on Vonda McIntyre’s novelization of Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home. Sometimes a plot that’s completely bananapants is the best kind.

Ellen Cheeseman-Meyer teaches history and reads a lot.

This book was clever in a way that’s only evident when you consider its historical context. It came out just after the end of Star Trek: The Next Generation‘s first season, and that means it was written while TNG was still just getting started. At the time, the audience knew that the Klingons would be at peace with the Federation in the 24th century, but very few specifics had been revealed yet. (All Dvorkin would’ve known at the time of writing was that the peace existed and maybe that there would be a Klingon crewman on the Enterprise; all the readers would’ve known at the time of publication was what “Heart of Glory” established, and that episode actually implied a more peaceful Klingon civilization than was later portrayed.) So at the time this book came out, it was plausible to the readers that Kirk actually had been transported to the 24th century and that the book was an indirect TOS/TNG crossover. It was a clever way to tell a story that came across as a TNG tie-in without the risk of contradicting anything TNG might actually establish by the time the book was released. No doubt that’s what inspired Dvorkin to come up with the Klingons’ “fake future” scheme to begin with.

Although the plot of making someone think they’re in the future in order to get them to give up intelligence secrets has been done before in fiction, for instance in two Mission: Impossible episodes — “The Freeze,” in which a mobster was tricked into thinking he’d been cryogenically frozen until 1980, the date the statute of limitation on his crimes ran out (with an uncannily accurate prediction of flatscreen TVs and home video), and “Two Thousand,” in which they trick a spy into thinking he’s in a post-apocalyptic dystopian future (making good use of a real-life earthquake-damaged location) so he’ll reveal the location of some stolen plutonium.

This!!

@2,

But how do we know that future historians will operate the same as current historians? I am reminded that historians in the late Roman Empire didn’t operate anything like a historian today.

This novel sounds like it used the movie 36 Hours as its inspiration.

From IMDB:

ISTR that the Germans kept James Garner in the hospital and didn’t let him wander around.

Speaking of M:I, there’s an episode where a criminal is tricked into thinking he’s gone back in time, so that he’ll reveal where a murder victim’s body was hidden. The tricked criminal was played by… William Shatner!

And one of the better 5th season episodes of Six Million Dollar Man, “A Matter of Time”, featuring John De Lancie.

@5/rickarddavid: Yeah, that episode didn’t work as well for me as the “faked future” episodes. A good con is one that’s plausible for the mark, something they’d already be inclined to believe. Who the heck is ever going to believe they’ve suddenly woken up 30 years in the past? He should’ve known right away that it was some kind of deception.

By the way, is it intentional that Tor.com posted this review of the Trek novel Timetrap just three days after posting the Rewatch of the animated Trek episode “The Time Trap”? Confusing, isn’t it?

#4

Yes, and that movie was inspired by “Beware the Dog,” a short story by Roald Dahl. A good read.

History at its best is concerned with recording what happened not commenting on it and certainly not taking political stances. The federation historians are the best kind of historians and the fact they exist as they do is part of the reason for the peace and high mindedness of the federation. History is not and should not be about politics.

@9 – Balderdash.

@9/dwcole: You’re making a false dichotomy. It’s not like the only choices are mere cataloguing and arguing a political agenda. History is about analysis. It’s about trying to figure out why things happened rather than just reporting what happened. Yes, often the theories offered to explain historical processes and events can have a political slant to them, but not all the time. More generally it’s just about trying to understand the reasons for things. History is a science, and science is about finding explanations rather than just listing facts.

Ow, poor Kirk. I read the book when it was new, but I didn’t remember the part about the injuries, only the fake time travel plot.

The fake Organian sounds silly. The fact that something looks like a cheap special effect to the audience shouldn’t mean that it looks like a cheap special effect to the characters.

I’m not sure if I agree with the criticism of Star Trek historians. An important part of a scientist’s work is the collection of data. Lots and lots of very detailed data. So of course that’s what a historian from the future would do when meeting a person from the past. The analysis comes later.

@12/Jana: I think Ellen was being sarcastic about the Organian “special effect.” It wasn’t actually described as looking cheap; it was some sort of holographic projection that Kirk found entirely convincing until he stumbled upon the machinery that generated it. Perhaps what Ellen meant was that it simply needed to be a blinding ball of light, with no further detail needed, which would’ve made it relatively easy to project as an illusion.

@13/Christopher: Thanks for clarifying that. I shouldn’t criticise plot points I don’t remember.

Was the fact that the Klingons needed drugs to act like humans handled convincingly? Because that seems wrong to me too. Klingons didn’t behave all that differently from humans in TOS, and there was a Klingon spy disguised as a human in “The Trouble With Tribbles”.

I like that this is a Star Trek version of “Beware of the Dog” (as pointed out in comment #8), two years prior to TNG’s “Future Imperfect”.

@14 – I agree wi put your point in re. The Trouble with Tribbles. I guess the spy could have been drugged, but that didn’t come up in either story. Kor also didn’t seem like he was incapable of being in human company – he offered Kirk a drink. T

@14/Jana: I haven’t read the book in ages, but I do have the impression that I felt it was a bit simplistic in its assumptions about the inflexibility of Klingon behavior. I felt all three of Dvorkin’s Trek novels (the others being The Trellisane Confrontation from 1984 and TNG: The Captains’ Honor with his son Daniel) had concepts that were a little off-kilter in their interpretation of the Trek universe or that stretched credibility too far. For instance, the TNG novel was a sequel to “Bread and Circuses” that reinterpreted the Roman planet, which was explicitly the fourth planet of its system and merely similar in its land-water ratio to Earth, as being an exact duplicate of Earth and its history in every detail up until the coup attempt of Sejanus, which failed on Earth but succeeded there. (Which was an in-joke I didn’t get for years, since Sejanus was Patrick Stewart’s character in I, Claudius.)

Honestly, I wasn’t that fond of any of the Dvorkin books, although Timetrap was the one I had the highest opinion of.

The Dvorkins were a great team in getting my book self-published. David really knows sci-fi and book cover design.

http://www.dvorkin.com/stephentheberge

@15/EllenMCM: Good point! Kor even talks about how similar Klingons and humans are. It’s Kirk who insists that “we’re nothing like you”.

@16/Christopher: Then I won’t read the others.

But I did reread the beginning of this one and was surprised that it takes place after TVH. It mentions Kirk’s reading glasses, among other things. The “particularly young and dewy-looking Kirk” on the book cover is completely wrong.

@16. Chris,I am surprised you did not mention that Peter David did the “fooling him he went backward in time” plot in his run on the Incredible Hulk. In fact it was for the character’s 30th anniversary. Either issue 392 or 393. You have mentioned him using other’s concepts before on here. In fairness to David,he always acknowledge’s when he uses others ideas. For instance you mention the third annual about Scotty’s wife. The first page says the concept was taken from a Harlod Pinter play. And Jones slyly mentions the fact that the idea came from Mission Impossible. Do not know the issue about the MASH inspired issue.

The fourth and first time he took another concept was a early Spectacular Spider-Man issue about a bank robbery. The concept was from Kurosawa’s Rashmon. This is shown by having Rashmon as the name of the bank. He also mentioned on his webpage. He may borrow but he is honest when he does.

@19/Zeno: I’ve never actually gotten around to reading Peter’s Hulk run, though I’ve read his Hulk novel What Savage Beast, that basically continues the story the way he would’ve done it in the comics if he’d been allowed to. I probably should track down the collections at some point.